Forgetting for a moment

bloodshed in Syria

rabbits in labs

clubbed seal-cubs

that lamb with the pecked-out eyes

the world is as simple

as foxglove, skylark

this new dog rose, creamy

scent of honeysuckle

where here from the warm dark soil

nubs of beans rise hump-backed

cotyledons poised like lungs

or stubby wings

before it all floods in again

come roost in my heart

bean, lamb, broken-bodied child –

may it be big enough

to hold you all

Walking the Old Ways : nature, the bardic & druidic arts, holism, Zen, the ecological imagination

from BARDO

The stars are in our belly; the Milky Way

Is it a consolation

is star-stuff too?

– That wherever you go you can never fully disappear –

Tree, rain, coal, glow-worm, horse, gnat, rock.

Roselle Angwin

Thursday 31 May 2012

Monday 28 May 2012

love & death in the forest

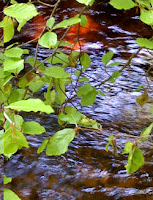

The leat – or narrow canal – in the Forêt de Huelgoat fascinated me. It was murky-brandy-coloured in the way that Dartmoor streams are (due to the granite bedrock, maybe? Or the minerals that co-occur with lead and silver?), and the dark opacity seemed to add huge depth and subtlety to the surface colours. Shafts of sun slanting through beech and chestnut and oak lit it with a deep glow. I must have taken 70-odd photos of its surface, to TM's impatience.

Originally the leat channelled water 6kms or so from the Moulin de Chaos to drive the great wheel at the silver and lead mine in the forest. Now one of the two conduits peters out; the other has been diverted to power a hydro-electric scheme.

We followed a part of the leat the first evening, by accident, on our arrival, deep towards the dusky woodland heart. On our second day walking we picked up the leat on our return.

On our way out that day we followed the course of the main river, slightly higher up (I can't remember if this one is the Arquellen or the Argent – they both pass through the forest).

Leaving the wooden café, we headed off on Le Sentier des Amoureux, Lovers' Lane, with the river murmuring away below and to our right.

Just over the hill from us was the Iron Age Camp d'Arthus, of a type Julius Caesar mentioned in De Bello Gallico as typical of this area, of Gaul.

All was tranquil, sunny, birdsongy.

Then suddenly we were taken into death. A small granite plaque by the footpath alerted us to a monument just above us on the hillside commemorating three village men from the Resistance taken out and shot by the Nazis in this beautiful leafy place.

It's the more shocking because the monument is half-camouflaged by trees, and the plaque small and simple; without the latter you might not notice the stone. Undoubtedly, illogically, it has even more impact because the woods are so beautiful.

I can't help being aware of the incongruity, or poignancy, of the naming of this footpath with its shadow of executions as 'lovers' lane' – who knows which preceded which?

We're silent for a few minutes. I muse on the many connections between love and death. In this case, there was a direct correlate: love of freedom and homeland, and presumably of the people whose lives the resistance fighters were protecting. Commitment to a cause bigger than themselves, no matter what the cost.

I think about the words for 'love' in French, and for 'death': 'l'amour' and 'la mort' respectively.

I think about how the French call sex, or orgasm, 'la petit mort' – the way something of the separate ego dies in the moment, for the moment.

I think of how in order to truly love we have to be prepared to die over and over: to our old lives, to our resistances, to our negative habits and behaviours, to our selfishness, to our attachment to our separate selves and the dictates of ego.

I think of the canal: always and never the same; how a body of water in its changing still contains all the drops that make it up; how none is ever lost, but all lose or change their identity in the whole.

Sunday 27 May 2012

bread

Travelling back across Dartmoor on a stunning May day with summer having suddenly hatched from spring and all the pony foals well-grown already, I switch on BBC Radio 4, a luxury for me these days.

A voice I recognise, albeit not named, is speaking about bread. I didn't copy this down so it's a paraphrase, but it's pretty close to Satish Kumar's* original words:

'Bread is the macrocosm's micro-. The sun is in bread. The moon is in bread. The rain is in bread. The soil is in bread. The farmer, the baker, the eater are all in bread. Bread contains all the elements, and for that reason it's the macrocosm in miniature.'

After that a Frenchman is speaking about the significance of bread; and how until, I believe, the late 1980s bread was deemed sufficiently important to have its price capped by the government.

I love the fundamental simplicity of all this; the stapleness of bread.

In our household we usually make bread in the machine; we only eat our own bread, and we don't live close to shops so homemade bread is a genuine staple. This way we know that the bread we eat is wholesome organic wholemeal, with no rubbish added.

I use spelt flour, the 'neolithic' flour, a genuinely ancient variety, as I seem to have a sensitivity to ordinary wheat, which is a (relatively) late addition to the British diet. I've found out recently that a wheat intolerance is common among the Celtic peoples: our local grain would have been barley, oats or rye, as ordinary wheat doesn't grow so well in the Celtic fringes (presumably spelt was a much earlier introduction to the British Isles).

There's friendly rivalry between TM and I. Even using a machine the results are not foolproof. In my mind an ideal loaf is high and domed. Usually, although I get the height I don't get the dome; and if I do the bread crumbles too easily. I like to add eg onions and fresh herbs, or olives and sundried tomatoes, or flax seed, pumpkin seed and walnut; or raisins and berries.

TM's loaves until recently didn't rise much and were, for my taste, a little damp and holey. He's snotty about adding anything except walnuts or maybe pumpkin seeds. Recently, however, he's cracked it: his loaves are domed (tick) but quite dense and low (hmmm) – but taste completely delicious. What's more, they hold together for sandwiches and toast.

Occasionally, though, I still make bread by hand. However delicious the machine-made bread is, it's nothing compared with the 'real thing', and shop-bought bread is so often almost a travesty (though I'm aware there's a flush of artisan bakers now in Britain).

Making bread by hand is almost a meditation; and the result extraordinarily satisfying. There truly is nothing like it. Try it, if you don't already. I promise it'll add all the baked-in elements – earth water air and fire – to your table. Share it with friends – that's the true meaning of 'companion': 'com pane', those with whom we share bread. Seems to me you could call breadmaking an act of love...

* Satish Kumar is an ex-Jain monk; the founder-editor of 'Resurgence' magazine, and the visionary behind Schumacher College.

A voice I recognise, albeit not named, is speaking about bread. I didn't copy this down so it's a paraphrase, but it's pretty close to Satish Kumar's* original words:

'Bread is the macrocosm's micro-. The sun is in bread. The moon is in bread. The rain is in bread. The soil is in bread. The farmer, the baker, the eater are all in bread. Bread contains all the elements, and for that reason it's the macrocosm in miniature.'

After that a Frenchman is speaking about the significance of bread; and how until, I believe, the late 1980s bread was deemed sufficiently important to have its price capped by the government.

I love the fundamental simplicity of all this; the stapleness of bread.

In our household we usually make bread in the machine; we only eat our own bread, and we don't live close to shops so homemade bread is a genuine staple. This way we know that the bread we eat is wholesome organic wholemeal, with no rubbish added.

I use spelt flour, the 'neolithic' flour, a genuinely ancient variety, as I seem to have a sensitivity to ordinary wheat, which is a (relatively) late addition to the British diet. I've found out recently that a wheat intolerance is common among the Celtic peoples: our local grain would have been barley, oats or rye, as ordinary wheat doesn't grow so well in the Celtic fringes (presumably spelt was a much earlier introduction to the British Isles).

There's friendly rivalry between TM and I. Even using a machine the results are not foolproof. In my mind an ideal loaf is high and domed. Usually, although I get the height I don't get the dome; and if I do the bread crumbles too easily. I like to add eg onions and fresh herbs, or olives and sundried tomatoes, or flax seed, pumpkin seed and walnut; or raisins and berries.

TM's loaves until recently didn't rise much and were, for my taste, a little damp and holey. He's snotty about adding anything except walnuts or maybe pumpkin seeds. Recently, however, he's cracked it: his loaves are domed (tick) but quite dense and low (hmmm) – but taste completely delicious. What's more, they hold together for sandwiches and toast.

Occasionally, though, I still make bread by hand. However delicious the machine-made bread is, it's nothing compared with the 'real thing', and shop-bought bread is so often almost a travesty (though I'm aware there's a flush of artisan bakers now in Britain).

Making bread by hand is almost a meditation; and the result extraordinarily satisfying. There truly is nothing like it. Try it, if you don't already. I promise it'll add all the baked-in elements – earth water air and fire – to your table. Share it with friends – that's the true meaning of 'companion': 'com pane', those with whom we share bread. Seems to me you could call breadmaking an act of love...

* Satish Kumar is an ex-Jain monk; the founder-editor of 'Resurgence' magazine, and the visionary behind Schumacher College.

Saturday 26 May 2012

migrating to Huelgoat Forest

*

The sea's dappled and glimmering, silk-smooth.

Dolphin conditions, we say

hoping that every

dark curve of wave

might instead be a sinewy back

Mid-ocean a small finch flits past, many miles from land; and then an hour later another. I guess they're on migration. I feel a moment's fear for their fragility, their distance from flock and land.

In another life, the life of a scientist, bird migration would have been my subject of choice. It is a wonder, a little miracle, the fact of bird migration.

Tell me how swallows navigate home

over and over

those few grams

against all the implacable ocean

(from Looking For Icarus, Roselle Angwin 2005, bluechrome)

Some say there's a kind of compass/lodestone in the bird's brain attuned to magnetic north. Some say birds navigate according to moon and stars. I've also heard, astonishingly, from a physicist dowser, that here in Britain waves crashing on the Western Atlantic seaboard send shockwaves through bedrock and the seabed that emerge as, I believe, infrasound, or at any rate as electromagnetic waves, high in the Ural mountains – and that wild geese navigate by these waves.

What's more, there is a deep knowing in the bird about where it needs to go, what constitutes home.

I find these things extraordinarily inspiring; and moving, too. A lone recently-fledged swallow, merely two or three months old, from a late brood here in England can find its way to where it needs to be by itself, for instance, despite that being another continent to which it has never travelled. And back again!

And here mid-ocean I'm aware that ships, and ferries like the one on which I'm sitting, save the lives of many exhausted migrating birds each year simply by offering temporary landing spots.

I'm on a 3-day migration to a favourite place: the magical Foret de Huelgoat in Brittany.

Brittany of course has much in common topologically (do I mean topographically?) as well as linguistically and culturally with the Celtic lands of Britain, especially the Western Celtic fringes. I read a very little medieval Welsh (part of my degree) and my father speaks some Cornish, so I can guess at some of the words and place names here. The Breton language is P-Celtic, or Brythonic Celtic, as are Welsh, Cornish and Manx (and maybe Galician); Scottish and Irish Gaelic tongues have Q-Celtic, or Goidelic, roots in common. In Welsh the word for 'wood' is 'coed'. Huelgoat incorporates the Breton word for 'wood', also 'coed' or 'coët', in its suffix 'goat' (consonants often mutate in the Brythonic languages depending on preceding or succeeding vowels). (If I ever knew what 'Huel' meant I've forgotten.)

Further south is the bigger and wonderful Foret de Broceliande, the Celtic enchanted forest of the Knights of the Round Table, Merlin the Sorcerer ('sorcerer' comes from the French words 'sourcier', one who divines for water), Vivianne, Morgana, Excalibur etc.

Huelgoat Forest is a much more modest but still utterly magical place, with its share of legends and Arthurian associations, as well as its magnificent long walks, one of our reasons for being here.

It reminds me of various spots on my local Dartmoor, from the moss-bedecked boulders with almost-fused little old oaks of the remaining ancient woodland to the deep gorges of Lydford with their 'devils' bowls' and roaring waterfalls. Here everything is larger-scale, and very lush. In the photo above, that opening in the rocks is man-sized; the path goes through it.

The path starts at the wonderfully-named Moulin du Chaos, the other side of the small road-bridge from this fierce concentration of water:

– not far from which two swans and their brood of six cygnets are paddling tranquilly. A small group of teenage boys looks to be considering whether to dare each other to jump. I'd have said there was little chance of surviving the huge tug and rush of the waterfall the other side turmoiling through the massive boulders in the gorge. I'm relieved that they've disappeared and there's been no siren by the time we pass by an hour or two later.

At the base of the huge boulders by the moulin (mill), where their rocky feet are in the stream, so to speak, a pair of grey (ie yellow) wagtails is performing astonishing backflips and nosedives, skimming flies from the threshold of air and water. Their solitary surviving youngster is perched on a low rock right above a huge fall of water waiting to be fed, tail flipping like a clockwork toy's.

This first evening, fresh off the boat, we take the path through the rocks with their fringes of bluebells and campions under tall chestnuts and beeches, the gold-leafed oaks; wander towards La Roche Tremblante, an enormous monolithic logan stone which, reputedly, if you lean against it at exactly the right spot, should rock slightly. We fail to make it rock, and smile ruefully at each other. (There follows a small and inevitable wisecrack by TM, which I'll spare you.)

Ahead, a red squirrel bounds up into the canopy. Below, the woods are settling into their non-human life of dusk.

We turn back to take another track through a small alley in the town, a circular trail past the tail-race of the leat –

– to find a creperie for that excellent Breton speciality, a crêpe de

blé-noir, or buckwheat flour, with creamy wild mushrooms and a salad.

(We find it in a small smoky ancient stone front room of the family-run

Crêperie de Myrtille.)

Through the half-open door the deepening sky is shrilling with swifts. A sliver of moon is considering make herself known.

I'm content.

This is also a home.

Monday 21 May 2012

cream of beenleighsoisse

We're off to Brittany (Huelgoat forest) for three days on a cheap ferry deal. Hooray. I feel very at home in Brittany, and I so need three days of hanging out, walking, reading, an occasional pavement café.

In the best Parisian restaurants, I'm told, you pay an eye-wateringly large amount of dosh for an eye-teasingly small sherry-schooner quantity of chilled Vichysoisse soup (non-European readers, this is much smaller than, say, a wine glass). The soup is delicious, and is basically cream of leek, intense and deep pea-green.

Here, for you, is my mouth-wateringly tasty very cheap Cream of Beenleighsoisse soup:

Take:

Sauté in olive oil till wilted.

Grate into it some nutmeg, and add a good grind or four of black pepper.

Make up some stock with boiling water and stir in (make up with extra boiling water if needed to a depth of 1-2 cms above).

Simmer the whole lot for about thirty minutes, then whizz in a food processor or equivalent.

Season with salt to taste.

Add cream, after letting it cool a little; or I use vegan soya cream (delicious)

If you like, add a v small shot of sherry.

Enjoy with fresh bread.

In the best Parisian restaurants, I'm told, you pay an eye-wateringly large amount of dosh for an eye-teasingly small sherry-schooner quantity of chilled Vichysoisse soup (non-European readers, this is much smaller than, say, a wine glass). The soup is delicious, and is basically cream of leek, intense and deep pea-green.

Here, for you, is my mouth-wateringly tasty very cheap Cream of Beenleighsoisse soup:

Take:

- a leek (in our case home-grown organic – the last stand of these is seeing us through 'the hungry gap' in the veg garden)

- a handful of wild garlic, available in many leafy verges right now (OK bought garlic cloves if you must; say 2 or 3)

- a bunch of watercress (ironically we have a mass on the brook below us, commercial escapees, but the stream passes through sheep fields so there is the risk of the dangerous liver fluke parasite; I had to buy it locally)

Sauté in olive oil till wilted.

Grate into it some nutmeg, and add a good grind or four of black pepper.

Make up some stock with boiling water and stir in (make up with extra boiling water if needed to a depth of 1-2 cms above).

Simmer the whole lot for about thirty minutes, then whizz in a food processor or equivalent.

Season with salt to taste.

Add cream, after letting it cool a little; or I use vegan soya cream (delicious)

If you like, add a v small shot of sherry.

Enjoy with fresh bread.

The day I lost everything, by Fiona Robyn

With permission from Fiona from her and Kaspa's site 'Writing Our Way Home'

I stepped onto the train platform and felt

for the strap of my handbag.

My rucksack was there. The present for my

friend Heather was there. My tube ticket was there. Where was my handbag?

My handbag was gone.

I'd travelled early that morning from

Malvern to Paddington, and taken the tube to Charing Cross on the way to my

psychotherapy supervision training. I was half an hour away from the Tibetan

Buddhist centre where the training would take place. Without my handbag.

I went into action mode. I ran after the

disappearing tube to see if I'd left it on my seat - nothing. I walked quickly

to find a tube employee - who sent me to the mainline station, who sent me to

lost luggage, who said I'd have to call Paddington lost luggage. As I walked I

racked my brains. Could I remember taking my handbag from the first train? I

would rather it had been stolen, to save my embarrassment, but I had a horrible

feeling...

As I walked from place to place, I was

counting the loss. £160 in cash. My phone & all those numbers. My Kindle.

My iPod. My bank cards, driving license, all the cards in my wallet. My £70

train ticket home & travelcards for the weekend. My house keys. My filofax,

which contained my entire life - all my client appointments, all my addresses,

my schedule for the year. Gone.

I asked the train staff if they could call

Paddington for me - I had no money and no phone. My eyes pleaded with them.

They said they couldn't help me.

At this point, I realised that I had a

choice. I was feeling more and more panicky. I could either burst into tears,

schlep back to Paddington, cancel the weekend's training & go home with my

tail between my legs. Or I could take one step at a time and go forwards.

I went forwards. I carried on to my

destination. I arrived at my training (late) and announced to the group that

I'd had a disaster. They were all wonderful. The centre director looked up

numbers for me on his computer (Paddington lost property, my bank to cancel

cards...), the course leader leant me money for lunch, my husband got in

contact with Heather, I hogged the phone during the breaks.

It wasn't a great day. I felt waves of

panic, anger, feeling utterly stupid, fear of the unknown, despair. People kept

saying I was dealing with it all ultra-calmly, and I wondered if I was in

shock. I guess a Buddhist centre is a good place to practice non-attachment,

and here was my big opportunity...

I kept working with the feelings as they

arose. I thought 'one step at a time' or 'it's only money and inconvenience' or

simply 'let go'. My gaze kept returning to the huge shrine in the room we were

working in, and the three big golden Buddhas. I allowed myself to feel

supported by the universe. I'd be looked after, one way or another. I leaned on

my faith.

By the time I stood under the clock at

Waterloo station, waiting for my friend Heather, I felt better than OK. I felt

good. I had truly given up on getting back the contents of my handbag. I

thought they might recover my filofax, if I was lucky. I had let go.

As I waited, a man approached me.

"Are you

Fiona?"

"Yes?"

"I'm Pete.

We've got your bag."

They'd travelled from Malvern that morning.

They'd seen my bag left behind on my seat, and watched people walk past. They

thought, 'we have to do something'. They took it to lost property, who told

them they'd charge for me to collect it. And so they found my text message to

Heather on my phone, arranging when and where we were meeting. They'd been

trying to get in touch with her all day to let her know that they had my bag.

And then they'd COME TO MEET ME.

For the first time that day, I burst into

tears. I hugged them both. I'd let go of it all - my Kindle, my filofax, my

phone, my iPod, all that much-needed cash. And here it all was. Returned to me

- delivered to me on the other side of London - by strangers who wanted to do

the right thing. I could hardly believe it.

On my way back from London yesterday, I read

this:

"When we are forced to attend to the

places where we are most stuck, such as when faced with our anger and fear, we

have the perfect opportunity to go to the roots of our attachments. This is why

we repeatedly emphasise the need to welcome such experiences, to invite them

in, to see them as our path. Normally we may only feel welcoming towards our

pleasant experiences, but Buddhist practice asks us to welcome whatever comes

up, including the unpleasant and the unwanted, because we understand that only

by facing these experiences directly can we become free of their domination. In

this way, they no longer dictate who we are." (Ezra Bayda, from 'Beyond Happiness')

I know this to be true.

taking refuge on the edge

It's a truism, of course, that the only certainty is that our lives here are uncertain. We say it glibly. We know it's true. And (yet) we are all so often still driven by fear – largely, surely, of that which is uncertain, one way or another; and try to create structures against it.

And some of us also actively enjoy it, find it exciting, are driven by a vast desire to seek out all uncertainty's edges. I know, I'm one of the latter; and have paid for it hugely in gross ways, eg broken bones, and more subtle ways (eg in chronic restlessness). Finally, finally, for myself I recognise the significance of relating with more equanimity, from an altogether more harmonious place.

Again Buddhism has wisdom here. We can't change uncertainty, nor guard against it. All we can do is change our relationship to it to one more skilled, learn to dance with it. Avoiding it ('aversion') doesn't help; craving or courting it ('attachment') is the other pole.

As an ex-Roman Catholic, I have a love/hate relationship to ritual. Part of me, the pagan/shamanic part, is completely entranced by it (and I mean that in its literal sense; one of the aims of ritual, of course, is to create near-trance states, or entry into altered states of consciousness). Part of me, the Zen part, is more attracted to altogether simpler plainer practice with no distracting fripperies.

Ritual it seems goes back many thousands of years. Initially, I believe I'm right in saying, it was thought that shamanic ritual practice dated back at least 16,000 years (can't find Mircea Eliade's book to check); recent cave art discoveries suggest it might even be double that.

It is, I guess, a way of propitiating the gods, whether inner or outer.

The reason I'm saying this is that common to almost all Buddhist practice is the recitation of the Three Refuges: 'I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Sangha, I take refuge in the Dhamma (or Dharma)'. (The sangha is the community of Buddhist practitioners, the dharma is the Way or the Truth.)

As a disaffected teenager who'd left the Catholic Church, it was easy for me to replace the Catholic rosary with my Buddhist sandalwood mala, or prayer-bead string. As part of my rather erratic meditation practice I'd chant the Three Refuges in Pali (or was it sanskrit?) as a 'way in' to a meditational state of mind.

And yet, until just a few years ago, I had a deep resistance to the idea of 'worshipping' the Buddha as a kind of external deity-substitute, just as I'd had (and have) problems with the idea of worshipping God.

I also felt uncomfortable with the idea of 'taking refuge' – surely Buddhism wasn't about hiding from all there is?

For many years I'd been looking, nonetheless, for a statue of the Buddha for the garden – one that I really liked, one whose face wasn't too smug, too austere, too soppy-smiley. I found a small one in my local rural garden centre.

Gradually a profound change has happened in me. I am introjecting the quality of serene energy the statue radiates in the Buddha's face (OK it hasn't quite got to the surface yet).

In Buddhist thinking one is not 'worshipping' the Buddha. He is not a God, nor the equivalent of a Christ figure: Buddhism isn't monotheistic, and the Buddha is simply a symbolic representation of someone who's found enlightenment, and who shows the way to anyone else who wishes to do the work.

I knew this intellectually, and I knew that a Buddha figure is simply a reminder of the inner potential for peace and wisdom.

But I didn't experience this until much much more recently. It's only in the last few years of serious family illness and death that I have at last understood the potency of saying the Three Refuges at the opening of my meditation practice.

It is not, I discover, about 'hiding from' but about entering fully into the experience from a place of the Buddha-nature – that is in fully facing life's uncertainty without requiring it to be different, or to meet my needs, with – at last! – at least transient entry into being OK with that, being OK exactly with how things are, on this edge, right now. It's only taken me the best part of 35 years.

And some of us also actively enjoy it, find it exciting, are driven by a vast desire to seek out all uncertainty's edges. I know, I'm one of the latter; and have paid for it hugely in gross ways, eg broken bones, and more subtle ways (eg in chronic restlessness). Finally, finally, for myself I recognise the significance of relating with more equanimity, from an altogether more harmonious place.

Again Buddhism has wisdom here. We can't change uncertainty, nor guard against it. All we can do is change our relationship to it to one more skilled, learn to dance with it. Avoiding it ('aversion') doesn't help; craving or courting it ('attachment') is the other pole.

As an ex-Roman Catholic, I have a love/hate relationship to ritual. Part of me, the pagan/shamanic part, is completely entranced by it (and I mean that in its literal sense; one of the aims of ritual, of course, is to create near-trance states, or entry into altered states of consciousness). Part of me, the Zen part, is more attracted to altogether simpler plainer practice with no distracting fripperies.

Ritual it seems goes back many thousands of years. Initially, I believe I'm right in saying, it was thought that shamanic ritual practice dated back at least 16,000 years (can't find Mircea Eliade's book to check); recent cave art discoveries suggest it might even be double that.

It is, I guess, a way of propitiating the gods, whether inner or outer.

The reason I'm saying this is that common to almost all Buddhist practice is the recitation of the Three Refuges: 'I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Sangha, I take refuge in the Dhamma (or Dharma)'. (The sangha is the community of Buddhist practitioners, the dharma is the Way or the Truth.)

As a disaffected teenager who'd left the Catholic Church, it was easy for me to replace the Catholic rosary with my Buddhist sandalwood mala, or prayer-bead string. As part of my rather erratic meditation practice I'd chant the Three Refuges in Pali (or was it sanskrit?) as a 'way in' to a meditational state of mind.

And yet, until just a few years ago, I had a deep resistance to the idea of 'worshipping' the Buddha as a kind of external deity-substitute, just as I'd had (and have) problems with the idea of worshipping God.

I also felt uncomfortable with the idea of 'taking refuge' – surely Buddhism wasn't about hiding from all there is?

For many years I'd been looking, nonetheless, for a statue of the Buddha for the garden – one that I really liked, one whose face wasn't too smug, too austere, too soppy-smiley. I found a small one in my local rural garden centre.

Gradually a profound change has happened in me. I am introjecting the quality of serene energy the statue radiates in the Buddha's face (OK it hasn't quite got to the surface yet).

In Buddhist thinking one is not 'worshipping' the Buddha. He is not a God, nor the equivalent of a Christ figure: Buddhism isn't monotheistic, and the Buddha is simply a symbolic representation of someone who's found enlightenment, and who shows the way to anyone else who wishes to do the work.

I knew this intellectually, and I knew that a Buddha figure is simply a reminder of the inner potential for peace and wisdom.

But I didn't experience this until much much more recently. It's only in the last few years of serious family illness and death that I have at last understood the potency of saying the Three Refuges at the opening of my meditation practice.

It is not, I discover, about 'hiding from' but about entering fully into the experience from a place of the Buddha-nature – that is in fully facing life's uncertainty without requiring it to be different, or to meet my needs, with – at last! – at least transient entry into being OK with that, being OK exactly with how things are, on this edge, right now. It's only taken me the best part of 35 years.

Saturday 19 May 2012

silence, and Caesar's last breath

Well, it's no secret that I'm not often lost for words. But here you are witnessing such a phenomenon.

It's largely because the work we did together last weekend on my Zen and Poetry retreat, despite the brevity of a 24-hour retreat, went very deep; the well of silence from which we were drawing has remained to some extent present to me despite a rather harried, or at least jumbled, week. I'm no longing drinking from it actively but the quality of energy is vivid in my memory and imagination. (This came on the back of a week on Iona which also incorporated silence over a longer period.)

I'm increasingly using silence in my workshop programme. At first, as I know people often find it difficult, I was diffident about incorporating much silence. Now I'm a great deal more confident in its healing power, and I see a level of urgency in the world that requires this meeting place with stillness, with the non-verbal. People are really hungry for silence, and there's great relief for most people, perhaps after initial resistance, in dropping into the quiet spaces it opens for us. Silence refreshes all the parts, etc. And I'm reminded of how little there is, in truth, to say, that really matters – even as there's also so much.

And in addition just now as I was brooding on a gardening blog – current preoccupation the lack of germination of so many of our seeds, and the fact that something in addition to slugs has now eaten through our third replacement planting of broad beans, and the trials of being a right-on organic gardener who won't use products that negatively affect the rest of the ecosystem, and the trouble that causes since TM might like a little more pesticidal compromise than I find comfortable – just then, right now, TM delivered me a rather boggling fact that he tells me is mathematically modelled. Working out the implications of that is taxing my braincell: although I have little trouble believing/imagining the proposition, I do struggle a little with the computations.

OK, I've spoken before, rather glibly, in my creative writing, of the fact that we are breathing air shared by every other being in history, and recycled through a myriad of lungs and leaves trillions upon trillions of times since the earth became fit for organic life. 'You could be breathing air exhaled by Julius Caesar,' I've said in passing.

Do you know what the chances are of that being actually literally true? More than 98%. That is, there's more than a 98.2% chance that any one of us at this moment has at least one molecule in our lungs of the air/oxygen exhaled by Caesar in his last breath. (The model assumes an even distribution. By the way I'm not at the moment clear as to whether that's air, or oxygen specifically, and whether it makes a difference here.) Something to do with 10 to the power of 22: any one exhalation by any one person involves 10 to the power of 22 molecules of air. The total number of molecules of air in the earth's atmosphere, including those currently involved in breathing, is 10 to the power of 44. (If you understand this, and/or can elucidate, I'd be grateful. I'll follow the link though once TM's forwarded it, and post it here later as well.)

OK, after some explanation I get that 10 to the power of 44 is a Very Big Number and not just double 10 to the power of 22 (I failed my maths GCE twice). Nonetheless, what is preoccupying me is what does that say of the oxygen load within our atmosphere vs the number of people breathing it/the exhalation of carbon dioxide? And mammals and birds and reptiles and trees and plants... ah, you're there before me: trees exhale oxygen; oh but plant matter breaking down gives off carbon dioxide, doesn't it? And there surely is a difference between 'air' and 'oxygen' in the proposition...?

TM says 'Better to keep your mouth shut and risk looking like a fool than open it and prove you are.' Hmmm. Better go and seek the information. I might need to revise this post later. But there you go – looking foolish is not something that especially bothers me.

As I ponder all this I'm also opening Gillian Clarke's new book of poetry: A Recipe for Water. I love her work, and this has just arrived today. It promises to be a good one. Serendipitously I find this line: 'Words, made of breath, our chain of DNA.' (from 'Quayside')

Thursday 17 May 2012

this minute of eternity (Rumi)

We are the mirror as well as the face in it.

We are tasting the taste this minute of eternity.

We are pain and what cures pain, both.

We are the sweet cold water and the jar that pours.

Jalal al-Din Rumi, tr Coleman Barks

We are tasting the taste this minute of eternity.

We are pain and what cures pain, both.

We are the sweet cold water and the jar that pours.

Jalal al-Din Rumi, tr Coleman Barks

Wednesday 16 May 2012

balance of attention

In the Hebrides, just before I was due to run my retreat, I developed a tooth abscess which soon became excruciating. I was nowhere near a dentist, and for the first two or so days led the retreat anyway, until it became obvious (no sleep) that I needed to do something about it.

On a sunny morning, the day of our scheduled silent day-long walk to St Columba's Bay, I took the ferry back from Iona to Mull, where the lovely doctor gave me some antibiotics (I've almost never taken them in my life) on the strict understanding that I'd see my dentist here on my return.

It was a blue blue day, perfect for the walk; and because of someone else from the hotel on Iona needing the doctor, and therefore a lift, too, I missed the ferry. I'd said to the group to go ahead without me (the core group knew the way and the practice I make of the day) if I wasn't on the 10.30 ferry back – which I wasn't.

To my amazement, and my delight – this silent group walk is in a way the culmination of the retreat, and certainly a high point – when I arrived instead on the 12.20 ferry they were still there waiting for me on the sunny shoreside lawn, writing (the photo above was taken on a different and clearly more stormy day).

Now, back in Totnes, I take my abscess to my dentist. The antibiotics stopped the continual throbbing pain, and allowed me to bite, but the abscess is still very much present and very tender.

'Root canal work,' says Marchin. 'Has to be.'

And so it is. The needle is frighteningly large, there's a hefty dose of anaesthetic, and it's going right into the abscess which is alarmingly close to my cheekbone. PAIN. The work itself was ok, although the sensation of one's jaw being drilled into is – well, odd.

After, the dog and I went for a walk in the water meadows at Longmarsh – a new walk to me – next to the tidal Dart. All was well for about an hour, by which time the anaesthetic had worn off. Then there was a sudden intrusion of excruciating pain in my whole jaw, and then head and neck; a worse pain than the original one, that increased until I could barely think or walk, took over my whole body and awareness.

Now I know that actually this kind of pain is nothing. I've broken limbs and ribs, fractured my back, been through childbirth, suffered loss and death. I'm not a soldier on a battlefield; I'm not a kidnapped child. Of course, even in the middle of that pain, I had that perspective. But I couldn't think of anything other than getting back to the car, getting rid of the pain, going to sleep.

My whole attention was focused on the pain, and in my reaction to it ('PAIN BAD! PAIN BAD!), my resistance to it ('I DON'T LIKE THIS'), I lost myself, lost a sense of both centre and wholeness. Instead of keeping part of my awareness on the pain, on the experience, but reminding myself that it is not the whole, I could only think pain, and of stopping it. The beauty of my surroundings was completely irrelevant, what I had to do next ditto.

Then something extraordinary happened. Into my head flashed an image of a seal, and suddenly I knew for certain that I was about to see one. Though it is still tidal here, I have never before seen one here on the Dart this far inland by miles.

And yes, there right ahead of me, right by Totnes Bridge, in town, was a seal (being mobbed by gulls, as it happens). I had the privilege of seeing it, hearing the frothy wet whooooosh of its breathing as it dived, swam and emerged again, of watching it for long minutes.

Walking on, afterwards, back to the car my pain hadn't changed, but my relationship to it was utterly different.

What the seal brought me was an injection of intense joy – both for its presence, and for the fact that even in the middle of my pain, immersed in it, I was not immune to the attunement of self with universe – I knew I was going to see that seal before it happened.

And what that did for me was remind me of the potency of moments of joy, and the potency, too, of transience; and how in even extreme situations we can choose our response, and we can choose to bring in a balance of attention. 'Both this and this.' The universe is not my pain, and I don't need to shrink to fit my pain.

It also reminded me of the nature of our utter interconnectedness in the web of life at all times – how did I know I was going to see that seal? – and how small the cell of our individual life, and its small discomforts, is, when set against the whole.

While fully experiencing whatever it is I am currently experiencing I can still choose to remember it is never the whole picture, and this, too, will pass.

Tuesday 15 May 2012

writing the bright moment: zen & poetry mini-retreat

The deep silence of no words. I allow myself to fall into the well of it, with these others, companions on the journey.

Outside, the deep silence is the tumultuous hum of the earth with its many inhabitants here in this tranquil woodland garden; the air with its congregations of bird-voice; the rushy songs of millpond and leat, their registers and octaves. Wind whips and snaps the prayer-flags strung across the terrace – they belly and billow like sails, on the verge of leaving.

the way the dusk light falls rosy

on the flanks of Meldon

the way I have eyes to see it

the way the world unselfs me

On top of Meldon, shouldering cloud, a single sheep, like an unpenned thought.

At supper tonight below on the moonstruck millpond a single wild goose called the deeps over and over until the water answered with another.

These days I offer purchase to ivy / allow ladybirds to nest / in the cracks of my bark. / The wren's song / is also home

across the valley

the green path is a greenpaint finger

drawn across the russet hillside

now here

now there

it zigzags

all the way to the top

and then it keeps climbing

into pale dusk air

I am clad in the world / it lets me wear its technicolour selves / until we are all unselfed...

Thursday 10 May 2012

this moment

This has to be one of the most extraordinarily beautiful times of the turning year in the UK. Here in wet Devon everything is on the cusp of bursting into its fullest lushest becomingness, as green and juicy as it gets.

And the bluebell woods! The bluebell woods! The UK has half of the world's population of bluebells. Round here we still have the traditional deep ultraviolet single-stemmed native British one (as opposed to the showier stiffer paler Spanish interloper – the native one dates back at least to the Bronze Age and possibly the last Ice Age) with its delicate perfumed bellheads, and in the wet woods the scent and colour takes me to the edge of tripping-out.

Why is it, then, that I so anticipate this time of year – admittedly like every other time, but this quality of deep purple blueness against the acid green of the new beech leaves and the tawny-gold oak leaflets is unique; and yet it speeds past while I lose myself and the gift of this precious moment in the belief that there are other things more important to do than standing and gazing, than immersion in the deep heart of this one-and-only time of Right Now, Right Here? With what else do we offset our broken hearts at the troubles of the world?

Wednesday 9 May 2012

arrival on the island in 100 words with no 'e'

Ready for a bit of light relief? (That, dear readers, is a pun, as you'll see.)

Regular readers will know of my occasional practice of writing little journal-like pieces of exactly 100 words – a good discipline for someone who tends to over-wordiness. One of the most exciting creative projects I've been involved in was an email exchange with friend and fellow-poet Rupert Loydell. We agreed to co-write 100 prose poems of 100 words in 100 days. This was a very inspiring and catalysing process, and the result was published as A Hawk Into Everywhere (currently out of print, but watch this space). It seems to have inspired a number of other poets, and other collaborations. I'm very proud of it.

One of the things I do with my various writing groups is to attempt to inject a little of 'big sky mind' thinking (I refuse to say 'blue sky' thinking), with the aim of breaking our habits of expression. One of these is a piece of writing limited to 100 words, with one letter of the alphabet forbidden (this is a combination of an exercise of mine, one of Bernardine Evaristo's [I think] and something from the French oulipo poetic movement).

On Iona the task was to write 100 words on our arriving on the island without ever using 'e'. (I am ashamed to say we were very competitive at being first to spot who had slipped up in the reading back – most of us, as it happens!) It's hard. And you have to find a new vocab. So like those foul-tasting cough medicines of our youth it probably does what it's meant to. Try it – use, say, 'this morning' as a prompt...

Here's mine:

Regular readers will know of my occasional practice of writing little journal-like pieces of exactly 100 words – a good discipline for someone who tends to over-wordiness. One of the most exciting creative projects I've been involved in was an email exchange with friend and fellow-poet Rupert Loydell. We agreed to co-write 100 prose poems of 100 words in 100 days. This was a very inspiring and catalysing process, and the result was published as A Hawk Into Everywhere (currently out of print, but watch this space). It seems to have inspired a number of other poets, and other collaborations. I'm very proud of it.

One of the things I do with my various writing groups is to attempt to inject a little of 'big sky mind' thinking (I refuse to say 'blue sky' thinking), with the aim of breaking our habits of expression. One of these is a piece of writing limited to 100 words, with one letter of the alphabet forbidden (this is a combination of an exercise of mine, one of Bernardine Evaristo's [I think] and something from the French oulipo poetic movement).

On Iona the task was to write 100 words on our arriving on the island without ever using 'e'. (I am ashamed to say we were very competitive at being first to spot who had slipped up in the reading back – most of us, as it happens!) It's hard. And you have to find a new vocab. So like those foul-tasting cough medicines of our youth it probably does what it's meant to. Try it – use, say, 'this morning' as a prompt...

Here's mine:

It’s light – limpid, viridian – almost solid in its fluidity, its glass quality, on which my boat is gliding. It’s light holding this ‘I’ up, supporting my swaying. It’s light picking out instants of colour on land – prisms of habitation, a hut, drawn-up hull, crab-pot, cat.

Landing in light. It’s light in a hug: almost-sibling to almost-sibling, warm, woman, loving.

It’s light calling lilac, fuchsia, apricot out of Fionnphort’s rocks, across this Sound, across a compass of shifting tidal drifts; drawing us out of cracks in which it’s our habit to burrow.

It’s light calling us back.

Landing in light. It’s light in a hug: almost-sibling to almost-sibling, warm, woman, loving.

It’s light calling lilac, fuchsia, apricot out of Fionnphort’s rocks, across this Sound, across a compass of shifting tidal drifts; drawing us out of cracks in which it’s our habit to burrow.

It’s light calling us back.

Tuesday 8 May 2012

interstellar dust mark 2 (the Buddhist take)

If you're a regular reader of my blog (and you perhaps don't know how much it means to me that some of you are), you may have noticed that I didn't include Buddhism, Zen or otherwise, in my thoughts yesterday. (For regular readers: some of what I write below is a reprise of previous posts, but reframed within this context.)

What I said yesterday was:

An evolutionary biologist would say that, improbable though it might

seem, consciousness such as ours has arisen like everything we know from

an interstellar explosion that created our planet, and the conditions

necessary for human awareness. Yes, the odds are billions to one, but

the process can be mapped.

A mystic would say that out of consciousness, universal consciousness, has arisen everything, including this planet and the conditions for us to emerge.

The gnostic or arcane/occult view might hold that everything we know and can know is a co-creation of the mind of the universe and our individual minds – that the universe needs us for its knowing as we need the universe for ours, and that that is a continual and continuing process of co-evolution.

A mystic would say that out of consciousness, universal consciousness, has arisen everything, including this planet and the conditions for us to emerge.

The gnostic or arcane/occult view might hold that everything we know and can know is a co-creation of the mind of the universe and our individual minds – that the universe needs us for its knowing as we need the universe for ours, and that that is a continual and continuing process of co-evolution.

The Buddhist view is compatible with all three of those statements – or at least has things in common with each of them; but differs also in a seemingly small but significant way. It is elegant, simple and radical in its scope and implications. The proposition put forward by Buddhism is that there is already in reality no separation between this 'me' and the rest of the universe. Our perception of duality, of 'me' versus 'you' or 'it', is the result of millenia of conditioned habituation to the notion of a separate egoic self, and our enormous efforts to preserve and defend our identity as this separate 'self'.

We

live, suggests Buddhism, in an utterly interconnected co-emergent universe, where everything is in a state of

co-arising all the time. (This co-arising also includes dissolution, but

in Buddhism these are not polar opposites.)

The Buddha famously would not be drawn into debate about

our cosmic origins, nor into stating absolute truths about the

universe. Buddhism doesn't tend to make statements about things that can't be relatively simply identified by individual non-expert experience, empirically. (Of course it requires attention and motivation.) I don't think this is widely recognised.

In brief, Buddhism in my view brings an active psychological dimension lacking, clearly, in the evolutionary biology approach, and largely absent as an active force in most other spiritual or religious traditions.

Central ideas in Buddhism include the convergences I mentioned in the

gnostic and mystic viewpoints. For Buddhism, everything is utterly

interconnected at all levels at all times, and it is only our

perceptions that hold us apart from that view and from everything else. (One could say, then, that our job is to pull back the clouds that obscure the already-in-place-ness of unity, which is perhaps the ultimate goal of all spiritual paths.)

Buddhism does not deal in beliefs that require eg faith. 'What I offer

is a way that leads beyond suffering,' the Buddha would say. 'Try it out

for yourself.'

What he was offering was a way of freedom based on awareness of and investigation into the psychological patterns that keep us back from being all we might be as spiritual beings, and prevent us from experiencing and giving out loving-kindness/compassion, and that can be experienced by anyone sufficiently motivated to try it out for themselves. If pursued with right concentration, effort and commitment, he suggested, it would bring about peace, serenity and a sense of unity – surely the aim of all spiritual paths – which would ripple beyond the individual self.

NB: the point is not salvation of an individual soul, but a contribution to the whole of committing to find ways to free us all from suffering, whether human, animal or planetary, and to the project of enlightenment. 'I vow to save all sentient beings', is the Bodhisattva Vow – not in the sense of believing oneself to be omnipotent, nor indispensable, but knowing that what one does for oneself one also does for others, and vice versa, in an interconnected universe; and, knowing that, to choose a path that is wise and 'skillful' (Buddhism avoids the binaries of eg good and evil, preferring a continuum between ignorance and wisdom).

It would also be true to say that Buddhism draws attention to the dangers of thinking one has found the 'one right way', and being caught in that belief.

For me, Buddhism is a psychological 'lens' for being skilfully present in the world and attempting not to fall into the traps and delusions of the ego – in other words, seeing the limitations of our habitual way of being in the world, and making choices based on an awareness that everything we think, say and do has consequences, and choosing response rather than reaction (I say again this is aspirational, but meditation and a commitment to mindfulness do keep the aspiration in view!). Through this lens I also practise a path that includes both gnostic/arcane and mystical elements.

So what prevents us from realising our true being, according to Buddhist thought, is our persistent belief in and defence of the existence of a separate self (or rather our locating our 'self' within the small compass of a separate ego), and the duality that brings in its wake. We divide the world into us and not us, this and not that.

In addition, we bring our judgements: good/bad, pleasant/unpleasant, love/hate and all the rest of them. Our identification with one pole and our reaction against the other the Buddha described as states of attachment or aversion which also keep us trapped in habitual patterns of thought, belief and behaviour, and are responsible for a great deal of the world's suffering and troubles.

And then there is the tricky notion of time; and the fact that we so rarely inhabit the present moment, as we're continually not only immersed in our sense of the little egoic self and its likes and dislikes, opinions and emotions, but we're continually lost, most of us, in nostalgia or regret for the past, or hopes and fears for the future.

Our need to cling on to things that simply cannot be permanent, our refusal to accept the obvious truth of transience, is another big delusion of the separate self.

So there we have it in extremely sketchy terms: what keeps us from knowing, experiencing, that we live in a co-emergent interconnected universe is that we buy into subject/object dualism instead of unity; that we miss the joys of the continuing present moment; that we hang on to our beliefs to define and keep separate the ego; that we don't accept the truth of impermanence.

Easy, isn't it??

Am off now to fall into the delusion of suffering at the dentist's...

Monday 7 May 2012

interstellar dust & us

| ||

| detail of star formation BLAST collaboration* |

If you were around in the 70s you might remember the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young song (was it written by Joni Mitchell?): 'We are stardust / We are golden / We are billion year old carbon / And we got to get ourselves / Back to the Garden...'

As an impressionable young romantic teenager, the notion that 'we are all stardust' was like a Big Bang in my mind.

My first short story involved some mystical quasi-post-apocalyptic God-figure quietly lying down to die [ie move to another level of consciousness] in a washed-up tide of dead fish that might also have been dead stars. I knew at the time the story was allegorical, and I was already steeped in ideas of the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, and the emergence of ecological thinking; I'm interested, having forgotten the long-disappeared handwritten story till the other day, to see now how many different layers of symbolism I'd incorporated without being fully aware of it, in some of the imagery.

I'd say the literal and metaphorical truths about our being stardust (like everything else we can experience in material form) have both shaped and given momentum to all my questing and thinking since then. This starfire burst, and how it connects everything to everything else! How we really are one another!

An evolutionary biologist would say that, improbable though it might seem, consciousness such as ours has arisen like everything we know from an interstellar explosion that created our planet, and the conditions necessary for human awareness. Yes, the odds are billions to one, but the process can be mapped.

A mystic would say that out of consciousness, universal consciousness, has arisen everything, including this planet and the conditions for us to emerge.

The gnostic or arcane/occult view might hold that everything we know and can know is a co-creation of the mind of the universe and our individual minds – that the universe needs us for its knowing as we need the universe for ours, and that that is a continual and continuing process of co-evolution.

The suggestion here is not that we humans are omnipotent, but that we may also be a way for the universe to know itself in our small localised sector of the all-that-is-consciousness. This view assumes, of course, that everything is consciousness, and that our experience of moving through time and space is one of continual and perpetuating relationship.

Whichever view one holds, isn't it the most amazing fact that we are here at all? Despite the degradations of death, war, sickness, poverty, homelessness, ecological disaster, abuse, neglect and cruelty this is still, as we averred in the hippy days, a beautiful world.

On a Bank Holiday Monday morning here in Devon, sitting at a round table and looking out at a courtyard wet with rain, alive with birds (including at the moment the stunt-flying of a pair of newly-arrived swallows), scented with bluebells, with life bursting green from every crack, I know that, despite the winter with its hard personal losses and deaths, I live in the Garden; the Garden is my home, and it's only my egoic views of separateness, of duality, my attachment to things staying the same, my requirement that there is no loss, no illness, no cruelty in the world, no death, that keep me from remembering this.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: '...we could say that it is our nature and calling, as sentient beings, to regard our situation with awe and wonder, and to wonder deeply about the potential for refining our sentience and placing it in the service of the well-being of others, and of what is most beautiful and indeed most sacred in this living world – so sacred that we would guard ourselves much more effectively than we have so far from causing it to be disregarded.' (in Coming to our Senses)

I'd say the literal and metaphorical truths about our being stardust (like everything else we can experience in material form) have both shaped and given momentum to all my questing and thinking since then. This starfire burst, and how it connects everything to everything else! How we really are one another!

An evolutionary biologist would say that, improbable though it might seem, consciousness such as ours has arisen like everything we know from an interstellar explosion that created our planet, and the conditions necessary for human awareness. Yes, the odds are billions to one, but the process can be mapped.

A mystic would say that out of consciousness, universal consciousness, has arisen everything, including this planet and the conditions for us to emerge.

The gnostic or arcane/occult view might hold that everything we know and can know is a co-creation of the mind of the universe and our individual minds – that the universe needs us for its knowing as we need the universe for ours, and that that is a continual and continuing process of co-evolution.

The suggestion here is not that we humans are omnipotent, but that we may also be a way for the universe to know itself in our small localised sector of the all-that-is-consciousness. This view assumes, of course, that everything is consciousness, and that our experience of moving through time and space is one of continual and perpetuating relationship.

Whichever view one holds, isn't it the most amazing fact that we are here at all? Despite the degradations of death, war, sickness, poverty, homelessness, ecological disaster, abuse, neglect and cruelty this is still, as we averred in the hippy days, a beautiful world.

On a Bank Holiday Monday morning here in Devon, sitting at a round table and looking out at a courtyard wet with rain, alive with birds (including at the moment the stunt-flying of a pair of newly-arrived swallows), scented with bluebells, with life bursting green from every crack, I know that, despite the winter with its hard personal losses and deaths, I live in the Garden; the Garden is my home, and it's only my egoic views of separateness, of duality, my attachment to things staying the same, my requirement that there is no loss, no illness, no cruelty in the world, no death, that keep me from remembering this.

Jon Kabat-Zinn: '...we could say that it is our nature and calling, as sentient beings, to regard our situation with awe and wonder, and to wonder deeply about the potential for refining our sentience and placing it in the service of the well-being of others, and of what is most beautiful and indeed most sacred in this living world – so sacred that we would guard ourselves much more effectively than we have so far from causing it to be disregarded.' (in Coming to our Senses)

*by the international research team that built an innovative new telescope

called BLAST (Balloon-borne Large-Aperture Sub-millimeter Telescope); sciencedaily.com

Friday 4 May 2012

we are one another

This darkish exuberance of spring rain! The face of the little brook is rain-pocked. Many registers make up the song of the small cascade: if I listen with all of myself I can hear their divergence and singularity as well as their convergence.

The woods' margins are a charm of thrushsong, goldfinch, bullfinch. A single yellowhammer flips over the hedge.

Beech leaves have begun their acid-green emergence into air, water, light. Dog and I are kneedeep in ramsons and bluebells, lit by the occasional creamy wild arum. Each time we come to a storm-felled tree across the path, its continuation the other side is a little wilder, a little more dense with bluebells until we're wading in an ultraviolet stream into the heartlands.

My many selves run ahead of me into their own thoughts, into yesterday and tomorrow, leaping recumbent tree trunks and little ravines carved out by rain. From time to time I gather them back and we walk together in the present moment, in presence.

I have no hat on and I let the rain enter all of me. We are one another. That is simply how it is. The discriminating mind thinks 'me', thinks 'you'. In this moment I am also, for a moment, the rain; as I am the fresh hoofprints, again, of roe deer and the passing deer that made the prints.

And of course then again I am 'me', this conglomeration of waves and particles, walking here in Larcombe Woods, alone and never alone. I crave what we all crave: this dropping of the ego-barriers, this dissolving into and out of all space and time at once, this slipping of the leash of separateness.

Beside me, a wren whirrs our of the ivied ruined walls of the old quarryman's cottage. Ahead, the path gives out. I've reached the human limits here: the huge oak, long-felled across this particular path, has a girth and limbs beyond my climbing power. Below, the pond is today a tarnished mirror, murky, muddy, a receptacle for whatever I wish to impose on it simultaneously with being its own distinct watery self.

The bodhi is not like a tree

The mind is not a mirror bright;

If there is nothing from the first

Where can the dust alight?

My boyfriend scribed that Zen koan in a card to me when I was 16 (you could call him spiritually precocious). I'm still considering the paradox of being and non-being.

The woods' margins are a charm of thrushsong, goldfinch, bullfinch. A single yellowhammer flips over the hedge.

Beech leaves have begun their acid-green emergence into air, water, light. Dog and I are kneedeep in ramsons and bluebells, lit by the occasional creamy wild arum. Each time we come to a storm-felled tree across the path, its continuation the other side is a little wilder, a little more dense with bluebells until we're wading in an ultraviolet stream into the heartlands.

My many selves run ahead of me into their own thoughts, into yesterday and tomorrow, leaping recumbent tree trunks and little ravines carved out by rain. From time to time I gather them back and we walk together in the present moment, in presence.

I have no hat on and I let the rain enter all of me. We are one another. That is simply how it is. The discriminating mind thinks 'me', thinks 'you'. In this moment I am also, for a moment, the rain; as I am the fresh hoofprints, again, of roe deer and the passing deer that made the prints.

And of course then again I am 'me', this conglomeration of waves and particles, walking here in Larcombe Woods, alone and never alone. I crave what we all crave: this dropping of the ego-barriers, this dissolving into and out of all space and time at once, this slipping of the leash of separateness.

Beside me, a wren whirrs our of the ivied ruined walls of the old quarryman's cottage. Ahead, the path gives out. I've reached the human limits here: the huge oak, long-felled across this particular path, has a girth and limbs beyond my climbing power. Below, the pond is today a tarnished mirror, murky, muddy, a receptacle for whatever I wish to impose on it simultaneously with being its own distinct watery self.

The bodhi is not like a tree

The mind is not a mirror bright;

If there is nothing from the first

Where can the dust alight?

My boyfriend scribed that Zen koan in a card to me when I was 16 (you could call him spiritually precocious). I'm still considering the paradox of being and non-being.

Thursday 3 May 2012

post-beltane beltane post

The Levels, May Day

(reprise)

i

Not a leaf moves; not a

bird calls.

I

don’t know how long

we stare at each other.

We

don’t know how long we have.

There is a drumbeat

passes

from cell to cell

a hot wind hopscotching

over

the synapses.

ii

Listen – somewhere there

is a question

knocking and knocking.

Silence your heart

and

listen

with

all of yourself.

iii

Winds and moons that

drive you to madness

and

love

which

is always a form of madness.

iv

I

stand in the stream’s conversation

bruised wild carrot and water mint

wild

watercress peppery on my tongue

the

astringency of wood sorrel

buzzard lifting off from the broadcast drift of windflower and bluebell

something

squeaking in vain

Bel

is back in the watered sky

– and look, on the path, a glow-worm

drab

in the haze of daylight

recharging

its cells

for

its small terrestrial shining

its

pinprick contribution

to

the sum of light in the world

v

This

will go on

wherever

you are

wherever

or whatever I am

or

am not.

*

© Roselle Angwin, 2005

NOTES: this appears in All the Missing Names of Love, Roselle Angwin, IDP May 2012

Bel is an old name for the pagan sungod

Wednesday 2 May 2012

what nature manages without effort

High above me the translucent wings of seagulls against blue sky propel their bodies forward with no discernible effort, a rowing movement that seems almost mechanical. They simply move.

The little brook is swollen, pouring over the simple stone dam in a cataract of voices I can hear from the garden. 'The language of the hill country... or of any sacred place, is not the language of pen on paper, or even of the human voice. It is the language of water cutting down through the country's humped chest of granite, cutting down to the heart and soul of the earth, down to a thing that lies far below and beyond our memory.' (Rick Bass)

The dandelions this year are an exuberance, whole fields gilded. On the track I follow neat paired deer hoofprints up to the lane. In the lush Devon verge an early purple orchid has joined the orchestra of bluebell, campion, stitchwort. I rejoice in it, but it is simply being itself, in its beauty but unaware, I assume, of its beauty; swayed by the breeze, in among its 100s of neighbours, flora and fauna.

Jeanette Winterson: 'Very few people ever manage what nature manages without effort and mostly without fail. We don't know who we are or how to function, much less how to bloom. Blind nature. Homo Sapiens. Who's kidding whom?'

How old were we when we forgot that life does not have to be an effort? Or is it inherent in the taking-on of form?

How difficult this practice of stillness, of not striving, of quietude. Always I'm driven by the search for more: mine might not be an appetite for more materially, but it's just as much a craving as any other desire-driven hunger: in my case for more ideas, more experience, more words, more vibrancy, more relationality, more awareness, more moreness...

The challenge for me is to simply sit still, without reaching after anything, even effortlessness. (Today I am going to not try to not try to be effortless...)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2012

(199)

-

▼

May

(18)

- moment

- love & death in the forest

- bread

- migrating to Huelgoat Forest

- cream of beenleighsoisse

- The day I lost everything, by Fiona Robyn

- taking refuge on the edge

- silence, and Caesar's last breath

- this minute of eternity (Rumi)

- balance of attention

- writing the bright moment: zen & poetry mini-retreat

- this moment

- arrival on the island in 100 words with no 'e'

- interstellar dust mark 2 (the Buddhist take)

- interstellar dust & us

- we are one another

- post-beltane beltane post

- what nature manages without effort

-

▼

May

(18)